Presented for the first time at The Lock-Up in Newcastle, this is the most significant survey exhibition for Lebanese Australian artist Khaled Sabsabi. It features a fleet of works, from video installations to enamel paint and canvas, produced over a 12-year period, including never-before-seen works by the artist.

Sabsabi’s work presented here represents a diorama of the artist’s identity. Belief, devotion, and transcendence come together in fractals layered over the artworks in a sequence. The work shown is the result of an artistic practice spanning 20 years that pulls tangentially and geopolitically.

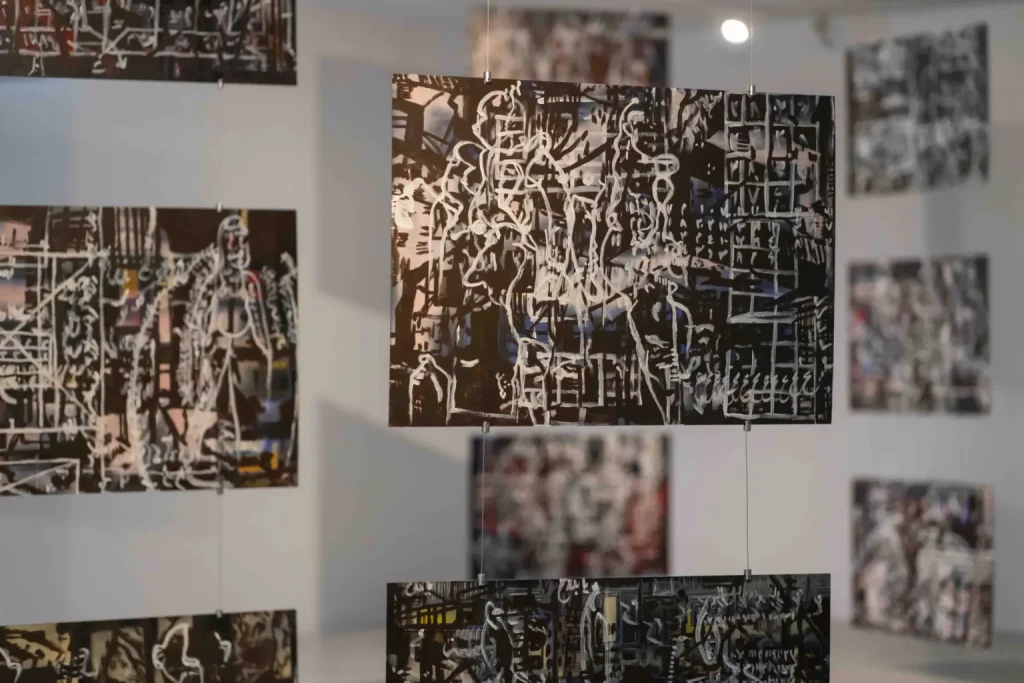

Here the pieces are presented in the inner sanctum of The Lock-Up’s converted shelter, previously a ground for prison inmates. Sabsabi’s body of work flouts symmetry in medium for texture. There’s a mishmash of audiovisual works presented alongside unstretched canvas and paintings that drip from wood and fabric.

Syria is the most established reference to this tension in the artist’s practice. The wood and sculpture installation shows sequential patterns in reference to his upbringing in slow motion, bleeding out into the darkness of The Lock-Up. The presentation melds into the space in a familiar yet strangely foreboding manner.

The artist reissues a held truth, that history is written by the victors, and that the significance of him displaying his work in a space such as this is not lost on him. God Complex is a pivotal piece in which Sabsabi illustrates this. Acrylic and enamel paint collide with hand-stencilled words. While the original work lives inside a lightbox, at the exhibition, it is the only illuminant in a pitch-black room. To that end, Sabsabi engages in the idea of restorative art – to create is to palliate the past.

A Selfie threads humanity and invites healing, and yet the title is very much a misnomer. The LED video installation playing on a loop only shows the crown of a man’s head haloed by light. We are uncertain if it is the artist, an unnamed subject, or the former rendering himself into the latter.

Sabsabi is the first to assume in his works that he, too, is a polyglot of many things too complex to be whittled into something Australian. The artist’s roots are everywhere: following the outbreak of civil war in Lebanon in 1975, Sabsabi migrated to Australia with his family, settling in Western Sydney, where he still lives and works today.

In artworks like 40, the details are not to be missed: the numbers marking all the hung artworks in the prison antechamber are bookends of his Islamic faith. Eighty smaller paintings accompany the triptych-style video installation, melding images of grainy dunes and sketches of a veiled woman, with flowers in place of their face. Sabsabi’s art probes at identity, interiorising the conflicts that occur when he travels from place to place. There are instances where these iterations land a touch literally, but they become resolved as the entire exhibition follows an arc that is traceable and moving to the viewer.

From analogue to digital work, Sabsabi has come a long way in honing his artistic methodology. “You come into the world as a stallion; don’t leave a donkey,” he advises. If such an exodus were upon Sabsabi, there is no instance where his legacy of work resembles his prevailing warning.

First published by ArtsHub on September 25, 2024. This article has been commissioned in partnership with Artshub for Diversity Arts Australia’s StoryCaster project, supported by Multicultural NSW, Creative Australia and Create NSW.