(First pubished as part of the BLEED Echo program, part of the BLEED festival.)

BLEED reminds us of the windows we have yet to create, fling open, or completely and irreversibly break down

I felt unprepared and under-dressed when I “entered” BLEED festival, on the 23rd of June 2020, the day after the festival had launched. I had just rushed back to my home in Minto from an orthodontic appointment to tighten my braces in the Sydney CBD, my teeth and gums clenching with pain as my mum handed me a hot pitha, telling me in Bangla to eat it “gorrom gorrom” (hot hot) and asking me whether I’d sanitised my hands before walking through the door. I answered her with the pitha smashed between my braces. “Yeah Alhamdulillah ammu, all good,” I said, unpinning my hijab as I walked to my bedroom, “I’m going to a Festival now though.”

There was a time when mum would have raised her eyebrows and asked me a dozen questions about this festival I was supposedly “going to” without leaving the house. She asked zero questions. Nothing surprises her in 2020.

Since news of the COVID-19 pandemic in March this year, I have experienced an overwhelming ‘blurring’ of people, places and experiences. In mid-March, I started a new job in the transport and infrastructure team of a law firm located in Martin Place. Within two weeks of starting, we were working from home. The chair I sit on as I proofread contracts about the construction of Sydney Metro is the same chair I sat on to write poems about faith and feminism for my English Extension 2 project in 2012. I have started to develop relationships with colleagues in my team who I have only met through Skype video calls and GoToMeetings. The line between ‘work’ and ‘home’, ‘colleague’ and ‘friend’, ‘real person’ and ‘potential robot’ has become blurry.

“Rest is resistance,” Hannah says. “This time in the world is monumental. It’s so turbulent and yet so quiet all at once. The internal window I have found is swimming in my intuition.”

Hannah Brontë’s Mi$$- Eupnea urges audience members to seek out, and fling open, a window of clarity in an otherwise ‘blurry’ world where the internet forces us to occupy multiple ‘places’ at the same time. Close-up shots of foamy bubbles in waves combing in and out of a beach, red-orange flames flickering on top of blackened pieces of wood and overhead shots of the ocean bleed into each other as the narrators in each of the six immersive audio-visual works speak about the source of their ‘intuition’. The ‘um’s and ‘ah’s of the voiceovers, far from being edited out, accompany the sounds of gurgling waves and crackling flames. The voiceovers are not loud or imposing or quiet and overly performative. They are simply conversational – the exact volume and timbre a person would have if they were sitting with me on my bed, casually talking about how their intuition is tied to physical connections with the natural world. I feel migraines being peeled away from my brain as I watch the close-up shots of lime-green leaves on a palm tree, the veins on each leaf close enough to count. And all of this, I can experience while sitting, cross-legged in the comfort of my bed, with a cup of warm, peppermint tea in my hands.

When I tell Hannah about how her work has made me feel at ‘rest’, she encourages me to regard the act of rest as a defiant act.

“Rest is resistance,” Hannah says. “This time in the world is monumental. It’s so turbulent and yet so quiet all at once. The internal window I have found is swimming in my intuition.”

While mi$$-Eupnea urges an inward gaze, the remaining exhibitions force our gaze to the windows of possibility in the political and social movements occupying our headlines. As the coronavirus pandemic magnifies existing social and economic inequality in the world, as news of Black Lives Matter protests in Kenosha enter our Twitter feeds, with the name Jacob Blakereplacing the name George Floyd, and as industry leaders warn that we are “woefully unprepared”for the impact of climate change in coming decades, we are desperately in need of new solutions to redress deeply entrenched systems of racial injustice, climate change denial and economic inequality. Alex Kelly and David Pledger’s Assembly for the Future and James Nguyen and Victoria Pham’s RE:SOUNDING exhibitions demand that we break down centuries-old windows of white supremacy and one-dimensional thinking to instead perceive through windows designed and constructed by disenfranchised communities and communities of colour.

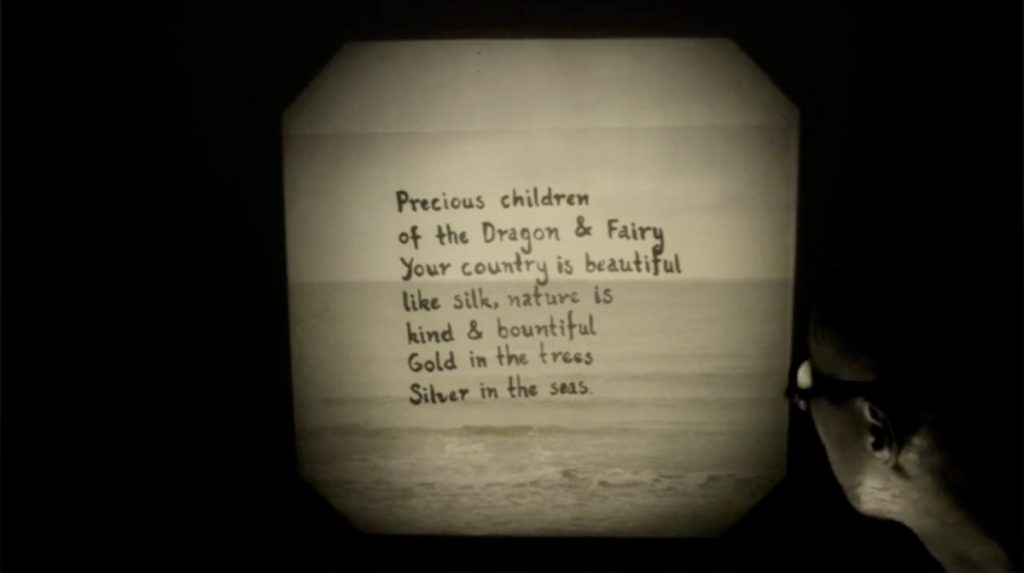

James Nguyen and Victoria Pham’s RE: SOUNDING reclaims the Đông Sơn drum from centuries of colonisation and cultural looting that had relegated the drum to the glass displays of museums across Europe. Despite growing up hearing stories from their mothers about the great, bronze Đông Sơn drums of Vietnam, James and Victoria first encountered these great drums as museum objects, to be looked at and read about, rather than as instruments to be played and heard. The BLEED Festival presented an opportunity for the world to reconnect with this 2000-year-old instrument.

“Knowing that you are a part of something, or directly experiencing something, even if it’s thousands of years or kilometres apart is especially reassuring in these times,” James tells me.

“The intimacies of care and connectedness, be they in digital form or in real-life, feed into our bodies, and hopefully this allows us to think, dream, and engage with the world beyond ourselves and the limitations that we encounter on a daily basis.”

In a Zoom call with Victoria, she tells me of the significance of RE:SOUNDING as an online exhibition celebrating the Đông Sơn.

“There’s not much left of ancient Vietnamese culture,” she says.

“If you look at Vietnamese history, we’re constantly going through layers and layers of conflicts. Often, when another regime would come in, they would destroy all the important artefacts that came before. However, because the Dong Son drum is solid bronze, it’s one of the rare things that has just managed to survive.”

James likens the displacement of the Đông Sơn drum “across the many soils and oceans of our new homes” to the displacement of Vietnamese people across the world. James and Victoria have produced 51 sounds from the Đông Sơn drum that they now make available through RE:SOUNDING STEMS, audio files which artists are encouraged to “re-sound”, thereby keeping the sounds of the Đông Sơn drum alive.

In each of the Assembly for the Future first speaker addresses, Alex Kelly introduces herself as the “keeper of time” chiming a silver bell for emphasis. Her heart-shaped earrings read “2020” and “2029”, the two years she is inhabiting in her and David Pledger’s exhibition. After an introduction comprising of awards and accolades mostly received between 2020 and 2029, Alex introduces keynote speakers for each of the assemblies – Claire G. Coleman for ‘Beyond Whiteness’, Scott Ludlam for ‘Somewhere, Everywhere, Right Here’ and Alice Wong for ‘The Last Disabled Oracle’. Like many people struggling to keep up with the horrific news each day of 2020, I have scarcely thought about the end of 2020 let alone the year 2029.

I found myself laughing out loud with joy and bewilderment as I witnessed adults play pretend in the Assembly for the Future exhibition, in a way that I have never seen before. The last time I had personally played pretend like this, I was seven or eight years old, sitting beside my little brother on the wide, metal swing in our backyard, pretending that we were on a quick aeroplane trip to Bangladesh, visiting our cousins. Occasionally, we would stop by “Japan”, “Canada” and, whenever I was grumpy with my little brother, “Poo-land”. If his shoe slipped onto the ground, I would tell him to leave it – “it’s somewhere in the ocean, now”. I felt that imaginative delight again as I watched these greatly esteemed writers and social justice activists speak to us “from the year 2029”.

“The last coal-burner got turned off three years ago. This is a renewable continent now,” says Scott Ludlam.

“The Disabled Oracle Society began in 2020 in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic when sick and disabled people sounded the alarm about the importance of wearing masks, the value of accessibility, and the interdependence of all communities”, says Alice Wong.

“By 2028 white supremacy had become a fringe belief, the world could finally heal from the ideologies that had ruined so many lives,” says Claire G. Coleman.

The truly wide-ranging ‘dispatches from the future’ exist in the same, ‘pretend’ universe of 2029. There are articles about the President of the United States of America, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the implementation of Universal Basic Income and poems about the turning point year of 2020, when the pandemic forced us to realise there was “living to be done”.

I asked Alex why she had centred the entire exhibition around this pretend universe of 2029.

“The device of operating ‘5 minutes in the future’ frees us from our fatigue with the present,” Alex says.

“Hopefully, it allows us to see that the future is never ever locked in – it is still up for being defined, for being fought for. When you speak with the authority of the future it does something to your body and to the body of the listener – we are transported, some part of us reacts differently to the possibility. This is the space in which we are attempting to make work – in the hope that it can unlock a place in all of us to fight for a liveable future for all rather than accepting the rampant inequality and violence of the present.”

Still from Becoming The Icon by Lilian Steiner and Emile Zile (image courtesy of the artists)

Where Assembly for the Future and RE:SOUNDING create windows for what could be, Angela Goh and Su Yu Hsin’s Paeonia Drive and Lilian Steiner and Emile Zile’s Becoming The Icon remind us of what is. Lilian Steiner and Emile Zile’s thirty-minute film cuts together performance sequences comprised entirely of their two bodies. No facial movement or dialogue until the very end, with the camera closing in first on hand gestures accompanied by voice overs, then bodies sluggishly wrestling on the ground, permanent markers on a blank piece of paper and then, finally, language, as our performers speak in a piece-to-camera for the first time, their faces devoid of emotion. In a world where fake news travels faster than the truth, and considering that it is an election year for the United States of America, Zile and Steiner’s film provides a timely deconstruction of how control over different parts of our body can in turn control the behaviour of those around us.

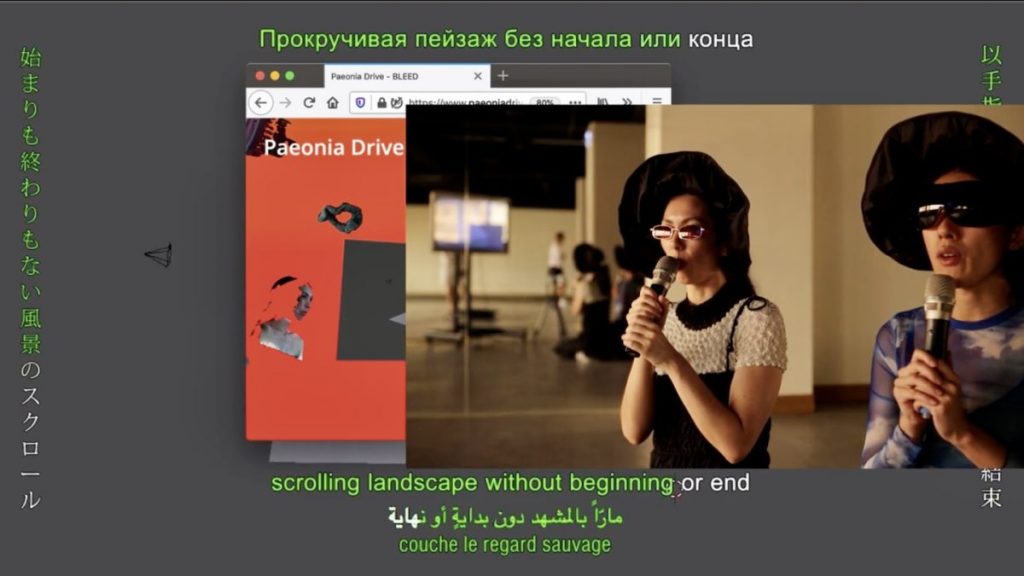

Similarly, Paeonia Drive explores themes of dehumanisation and control but from the perspective of technology and artificial intelligence. Their live-streamed desktop performance does not allow a single moment of ‘rest’. Every frame is crowded with window tabs, with each tab directing the audience’s gaze to a different perspective of the performance. In one tab, we see the two artists, Angela and Su, with microphones to their mouths as they read a script off-camera. As they speak, the English, Arabic and Japanese subtitles on the screen flash fluorescent green. Within this window we can see that they are in a dance studio, with a large mirror behind them reflecting the camera set-up and revealing another, blurry person in the frame. Behind this window lies another window, containing the BLEED Festival Paeonia Drive Virtual World page. Their droning, monotone voices, combined with the crowded audio-visual content on the screen is frankly overwhelming.

Despite feeling overwhelmed by the deluge of digital information presented in Paeonia Drive: Navigation, the performance signals a clear warning about the consequences of failing to draw adequate lines in the sand in relation to our dependence on the digital world; that we can become lost in the soup of the virtual space.

This warning about digital dependency is not inconsistent with the key messages of BLEED.

Although BLEED is an entirely digital festival, and one that we can revisit and reinterpret as we please, like any good artistic endeavour, each exhibition forces a re-interpretation of something beyond the artworks themselves – a window from which we can better perceive the outside world and the dangerous ‘norms’ that inform our everyday decision-making.

In a time of resistance, defunding and standstill, a festival like BLEED is a defiant act.

The words that Hannah Brontë left me with at the end of our interview fittingly reflect my own feelings of this festival as a whole:

“I truly feel a different tide is coming after this. Some very powerful healers in the world are stepping up quietly and fiercely, and I look forward to knowing them.”